Connections-Antifragile and Using the Eisenhower Matrix of Being Aware and not Being Aware/Knowing and Not Knowing

A connection between two abstractions. As least in my mind. An experiemtn that was fun to do.

The Author Nassim Nicholas Taleb coined the phrase Antifragile in his book of the same name (Taleb, 2012). The definitions of fragile, robust, and antifragile as given below are definitions that I cobbled together from Taleb’s work and my own understanding of the concepts.

Definitions

Fragile: Something fragile does not like volatility, randomness, uncertainty, disorder, errors, and stressors. Fragile systems crumble under high magnitude shock (perturbations). Fragile systems prefer the deterministic, the known, and the familiar. Fragile systems prefer to operate in a rut and will suffer because of extrapolating solutions based on simple system assumptions to solve complex and uncertain systems..

Robust: Something robust is neutral to volatility, randomness, uncertainty, disorder, errors, and stressors. Robust systems can successfully survive and resist the high magnitude shock (perturbation); although they will only maintain the status quo at best, they will not get better or gain from the situation.

Antifragile: Something antifragile thrives on volatility, randomness, uncertainty, disorder, errors, and stressors. Antifragile systems will not only survive but will benefit from the high magnitude perturbation. In this case, the gains and benefits from perturbation will be nonlinear, i.e., the benefits stemming from the perturbation can increase nonlinearly.

I had written about applying the concept of antifragility in the volleyball context a few years ago. (https://polymathtobe.blogspot.com/2022/09/antifragile-volleyball-antifragility.html) I also started playing with using a variation on the Eisenhower Matrix to examine the categories of personal knowledge around the same time. This analysis of the state of my personal knowledge came about during one of my many omphaloskepsis sessions. I was not thinking about the state of knowledge writ large, but personal knowledge — about what I know and whether I was aware of my knowledge or not. I made the connection between the two ideas and started thinking about how I can utilize my Eisenhower matrix-like knowledge analysis of what I know and do not know coupled with whether I was aware of knowing or not knowing to train myself to reach a state of antifragility.

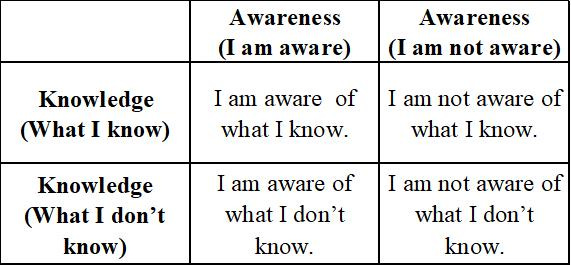

I put the matrix below together to help track how awareness and knowledge and how they would interact. The two-by-two matrix illustrates the interaction of the two variables. In this case, the two variables are two different levels of cognition. One level involves awareness (The top row) and the other involves actual knowledge. (The left column).

Even though the Eisenhower matrix structure gives us four neat quadrants to categorize our awareness and knowledge, reality isn’t so cut and dried, there are considerable grey areas between the four quadrants. More on that later.

Quadrant (1), (I am aware of what I know), unequivocally stakes the territory of the known. My own awareness of knowledge that I have.

Quadrant (2), (I am aware of what I don’t know), takes us to the realm of our own ignorance. For some, this is a difficult quadrant to parse, because the same bias, fallacies, and hubris that affect our decision making will also keep us from admitting to any gaps in the depth and breadth of our knowledge. Although for some, it is the opposite of bias, fallacies and hubris: it is our own self-awareness and humility which causes us to understate the amount of our own knowledge, but that is rare.

Quadrant (3), (I am not aware of what I know), is a gift to us from us. The categorization often transitions from Quadrant (3), (I am not aware of what I know), to Quadrant (1), (I am aware of what I know), once we become aware that we DO have that knowledge. The revelation is sometimes through serendipity and sometimes through unintended but deliberate and thorough searching of our long-term memory. This knowledge will sometimes come to the surface of our cognition as we are working on solutions to a new and unrelated problems, our minds will often make the connection, draw parallels and create the fortunate analogy to the knowledge that we know but are unaware that we know. We humans have this ability as a superpower: the ability to make connections, draw parallels, and create analogies, which allow us to take pertinent details from disparate ideas and synthesize new ideas from our existing experiences. This lead us to discover knowledge deep in our long-term memory that we were not aware of, but we had at our disposal all along.

A trivial personal example of quadrant (3), (I am not aware of what I know), comes from my memory of playing in a gradual student softball game. It was an excuse to take a break from working on our research to relax and drink beer while under the guise of socializing. I was placed in the short stop position, not because of my stellar athleticism, but because no one else wanted to be responsible for allowing the screaming liners through the hole or, more realistically, getting smacked ignominiously anywhere on the body by said screaming liner. True to form, someone hit a screaming liner to my right. I swiftly and deftly ran to my right — as swiftly and deftly as a fat guy can move — backhanded the ball and threw the runner out at first. I have never executed a play like that in my life, I had barely played softball in my desultory sporting life; nor have I ever executed that play again, ever. I stood there stupefied, wondering what had gotten into me. Everyone, including the people on the opposing team, were astounded, thinking that I was some kind of a ringer: a fat, slow, unathletic ringer. My fielding prowess for the rest of the game however, convinced them that I was no ringer. It was a skill that I never knew I had. I filed it under the blind squirrel finding a nut category. Quadrant (3) is the gift that keeps on giving, it gives that serendipitous thrill of discovery that makes uncertainty enjoyable. How do I explain my unexpected play? Watching endless hours of baseball on television while consuming massive quantities of soft drinks and chips as a child couch potato must have made my nervous system and body believe that I was capable of such a play. It never happened again because that was the last time I played softball.

Quadrant (4), (I am not aware of what I don’t know), is a reminder that the universe is infinite, uncertain, and difficult to know. A little reminder from the universe that relying only on what we believe to exist is not only foolhardy but idiotic. Even as we are doing what we think we are best at doing, there is a vast and random universe that surrounds us, and we are unaware of everything that exists in the vast and unknown world. Indeed, our biases, fallacies, and hubris drive us to believe that we know much more than we do. We need to constantly remind ourselves to check this transcendent box in our accounting of the universe so that we avoid being trapped by our hubris.

One of my former bosses becomes apoplectic whenever I talk about Quadrant(4), (I am not aware of what I don’t know). He tells me that he doesn’t pay me for being so negative. Most engineering managers I dealt with are programmed to think that the minion engineers who report to them could solve any problem if they only worked and thought hard enough, any failures come from not working and/or thinking hard enough to their taste. Yet we minions know that there are unknowable and unmeasurable parts of the universe which we must deal with, something that we frequently remind ourselves; we also know that singular and hard focus on a problem will only lead to circular thinking and delay breakthroughs, if there is one forthcoming. Indeed, something that I had learned as a young engineer when my experiments don’t behave as I expect them to, or when my assiduously calculated solutions fail ignominiously when applied to reality: Mother nature always wins.

Going back to the connection aspect between antifragility and the Eisenhower matrix I had just outlined, the question is: what could we do to use our kluged Eisenhower matrix analysis of knowledge so that we become more antifragile in our daily lives? What could and should we do with the way we think of our four quadrants to attain personal antifragility: to enable ourselves to thrive rather than just survive volatility, randomness, uncertainty, disorder, errors, and stressors. In this case thriving is defined as not just being able to survive but to benefit from the unanticipated perturbations.

The way that we deal with the four quadrants not only depends on our biases, our fallacies, and our hubris, it also depends on our ego and how far our hubris takes us. Those afflicted with the Dunning-Kruger Syndrome consistently over-estimate their quadrant (1), (I am aware of what I know), underestimate their quadrant (2), ( I am aware of what I don’t know), and ignore quadrants (3), (I am not aware of what I know), and (4), (I am not aware of what I don’t know). Those who suffer from the impostor syndrome will overestimate quadrants (2), ( I am aware of what I don’t know) and (4), (I am not aware of what I don’t know), while underestimating quadrants (1), (I am aware of what I know) and (3), (I am not aware of what I know). The rest of us will over or underestimate our quadrants differently every day, depending on the vagaries of how we feel about ourselves at that point in time.

A singular definition problem also exists to complicate our assessment of the four quadrants: the difference between knowledge and information. There are numerous quotes that I found on the internet that try to boil the idea down:

We are drowning in information but starved for knowledge.

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

The fog of information can drive out knowledge.

The essence is that information, or in the case of the last quote, data, is not knowledge. As the world wide web/internet has drowned us in information, it has not given us more knowledge, just more disparate and disconnected information to serve as cudgels to beat each other up in electronic one-upmanship and to become stooges to bots whose only purpose is to deceive and create false perceptions.

Yet another quote is:

The only source of knowledge is experience.

Which I would quibble with, sorry Albert. Knowledge is not just experience, but specific experience gained through applying and doing rather than just having experienced the information through thinking.

If I told you that I know how to change the oil in a car, that would be a fact. The truth of the matter is that I didn’t tell you how much I know or how skilled I am at changing the oil in a car. The fact is that I know ABOUT changing the oil because I watched my friend Randy change the oil in his car while we were chit-chatting in the parking lot of his apartment complex during a lazy Saturday afternoon while we were both gradual students, I have done it myself exactly once; even as Randy had tried mightily to talk me through the process, I made a bloody mess. I can BS my way through it because I remember the steps, but could I really claim that I know how to change the oil? Am I able to trouble shoot the oil-changing process if unexpected problems arise? Am I able to help someone else through the process? Probably not, not if I wanted to be honest. There is the matter of the relative breadth and depth of my knowledge, which is assumed but never declared; the breadths and depths of any knowledge are usually assumed by the person hearing me telling them about my oil changing prowess, at least until I am put to the test by demonstrating my “knowledge”. Our own biases, fallacies, and hubris, or lack thereof make me either claim this piece of information as a knowledge that I am aware that I know, which misleads those who take us at our word; or I can honestly admit that I only know ABOUT changing the oil in a car.

Going back to the connection between antifragility and the Eisenhower matrix analysis, the question that needs to be answered is: how do we prepare ourselves with our accrued knowledge so that we can thrive from unexpected circumstances?

Here is my personal list after some thinking, I am sure I am missing things, but I hope people will correct me.

· Be a generalist or a polymath, voluntarily expose your intellect to disparate and a broad range of subjects, expand your quadrant (1), (I am aware of what I know), and reduce quadrant (4), (I am not aware of what I don’t know).

· Be curious but be curious about both the depth and breadth of a subject, while also be curious to try to connect the results of the digging to your previous experiences. Turning quadrant (2), ( I am aware of what I don’t know) to quadrant (1), (I am aware of what I know)

· Be humble and triage quadrant (1), (I am aware of what I know), to filter out those things that you don’t have the depth and breadth of knowledge to rightly claim to know and move them to quadrant (3), (I am aware of what I don’t know). This takes a healthy dose of humility and self-awareness.

· Train to think extemporaneously, avoid thinking procedurally, be willing to take flights of fancy into unexplored and unknown territories. The human’s proclivity for practicality will always pull our thought process back to the practical and eliminate the impractical territories, but the experience from the flights of fancy reveals a connection, a parallel, and an analogy that is creative and new. This process needs to call upon all four quadrants personal knowledge. This is also the difference maker, where antifragility can be attained over just robustness, where we benefit from the perturbations rather than just survive them. The connections, parallels, and analogies are the magic that exploit the uncertainties, the contexts, and the nonlinearities to gain the advantage over the wicked environment.

Now that I have a framework , I can prepare myself for whenever I face unknown circumstances in the future. It allows me to wrap my mind around the way I view what I know and don’t know as well as considering my own awareness of what I know and don’t know. This framework also forces me to acknowledge that the quadrants that I have neatly drawn up are not so clear, and I need to accept the ambiguities that exist when I use this Eisenhower matrix to categorize knowledge. Fortunately, since I have already accepted the ambiguities of the abstraction that is antifragility, connecting to more ambiguities is not a huge leap.

I will be experimenting with this framework from this point forward, it should be quite a Curious Polymathic experience.

References

Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder . NYC: Random House.